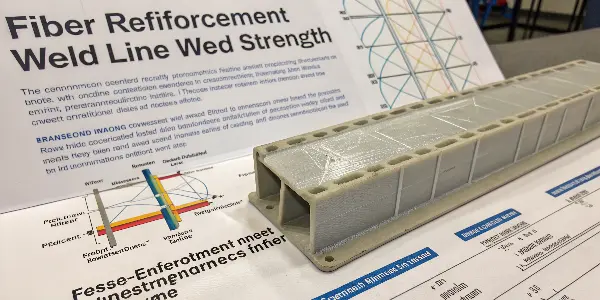

Are you struggling with parts that look strong but fail unexpectedly at a specific seam? This weakness, often found in fiber-reinforced plastics, can derail entire projects, wasting time and money. The problem lies where two plastic flows meet, creating a weak point called a weld line.

Fiber reinforcement significantly impacts weld line strength by creating a resin-rich, fiber-deficient zone. As two melt fronts meet, fibers align parallel to the flow, preventing them from interlocking across the seam. This creates a structural weak point. The solution involves optimizing mold design to relocate the weld line, adjusting processing parameters to improve fiber entanglement, and selecting materials that promote better bonding across the knit line.

It’s a frustrating issue. You’ve chosen a high-performance, fiber-reinforced material specifically for its strength, only to have the final product show a critical weakness. This single point of failure can undermine the integrity of the entire component. You need a reliable way to predict, manage, and ultimately strengthen these weld lines. But where do you start? Is it a problem with the material, the mold design, or the injection process itself?

Let’s break down the problem and explore the practical solutions we use here at CavityMold to ensure our clients get the high-performance parts they expect. We will look at how mold design, material choice, and processing all play a critical role in overcoming this common challenge.

Why Do Weld Lines Weaken Fiber-Reinforced Parts?

Are you seeing parts crack along a faint line under stress? This is a classic sign of a weak weld line. In fiber-reinforced plastics, this problem is much worse because the very fibers meant to add strength are often the cause of the weakness at these specific locations.

Weld lines weaken fiber-reinforced parts because the fibers fail to cross the line where two melt fronts meet. Instead, they align parallel to the flow front on either side. This leaves the weld line as a resin-rich area without the structural reinforcement of entangled fibers. The result is a significant drop in tensile strength and impact resistance at that specific point, making it the most likely place for the part to fail under load.

To really get a handle on this, we need to look closer at what happens inside the mold. Think of it like two rivers of logs flowing towards each other. When they meet, the logs don’t magically interweave; they just bump into each other and line up along the meeting point. The same thing happens with reinforcing fibers in molten plastic. This poor orientation is the root cause of the problem.

The Science Behind the Weakness

When we inject fiber-filled plastic into a mold, it flows from the gate and fills the cavity. If the design requires the flow to split around an obstacle, like a hole or a core pin, and then meet again on the other side, a weld line (or knit line) forms.

- Fiber Alignment: As the plastic flows, the long fibers tend to align themselves in the direction of the flow. When the two fronts meet, this alignment means the fibers lie parallel to the weld line, not across it. There’s no mechanical interlocking.

- Reduced Temperature and Pressure: By the time the melt fronts meet, they have cooled slightly and lost some pressure. This lower temperature and pressure prevent the polymer chains from fully melding and entangling with each other, leading to a weaker bond.

How Strength is Compromised

The mechanical properties of a part are directly tied to the fiber orientation. We can compare the strength at the weld line to the strength of the rest of the part to see the dramatic difference.

| Property | Strength in Flow Direction | Strength at Weld Line | Percentage Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tensile Strength | High (Fibers aligned) | Very Low | Up to 70-90% |

| Impact Resistance | High | Very Low | Up to 70-90% |

| Fatigue Life | High | Very Low | Significantly Reduced |

This table clearly shows why a weld line is not just a cosmetic issue; it’s a critical structural flaw that needs to be managed from the very first design stage.

Can Mold Design Eliminate Weld Line Weakness?

You’ve identified a weak weld line as the source of your part failures. Now, you’re wondering if you can just design the problem away. Can changes to the mold itself actually solve this fundamental material issue? You’re right to focus here, as this is your first and best line of defense.

Yes, mold design is the most powerful tool for managing weld line weakness. By strategically placing gates, you can move weld lines to non-critical areas where stress is low. Using larger gates, optimizing runner systems, and ensuring proper venting can also increase melt temperature and pressure at the weld line, promoting a much stronger bond between the two flow fronts.

I recall a project for a medical device housing that had to withstand repeated impacts. The initial design had a weld line right across a snap-fit feature, and it kept breaking during testing. Instead of changing the expensive, certified material, we ran a mold flow simulation. We found that by moving the gate from the center to the edge and adding a flow leader, we shifted the weld line to a flat, non-functional surface. The problem was solved without any other changes. This shows just how critical mold design is.

Strategic Gate Placement

This is your number one priority. The goal is to control where the melt fronts meet.

- Single Gate: Whenever possible, use a single gate to fill the cavity. This promotes a single, unified flow front and avoids weld lines altogether.

- Relocating the Weld Line: If you need multiple gates or have core pins, use mold flow analysis software to predict where the weld line will form. Adjust gate locations to move that line away from high-stress areas like corners, holes, or snap-fits. Move it to a thick, flat section where it won’t compromise the part’s function.

- Sequential Valve Gating: For large parts that need multiple gates, a sequential valve gate system is an excellent solution. It allows you to open and close gates in a specific sequence, controlling the flow of plastic to push weld lines to the very end of the fill path or out into an overflow tab, effectively removing them from the part itself.

Optimizing Flow Conditions

Beyond gate location, the design of the flow path itself is crucial for maintaining heat and pressure.

| Design Element | Standard Approach | Optimized Approach for Weld Lines | Why it Works |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gate Size | Small, for clean break | Large, full-round gates | Reduces pressure drop and frictional heat loss. |

| Runner System | Long, complex paths | Short, simple, full-round runners | Minimizes cooling and pressure loss before the melt enters the cavity. |

| Venting | Standard vents | Deep, full-perimeter vents at weld line | Allows trapped air to escape easily, preventing back pressure that hinders flow fronts from merging properly. |

By focusing on these mold design principles first, you build a strong foundation for a robust part and make any downstream process adjustments much more effective.

Do Processing Parameters Make a Real Difference?

So, your mold design is locked in, but you’re still seeing inconsistent strength at the weld line. You might feel like your hands are tied, but the settings on the injection molding machine are your next set of powerful tools. Can minor tweaks to temperature and pressure really change the game?

Absolutely. Processing parameters are critical for influencing weld line strength. Increasing melt temperature, mold temperature, and injection speed helps the two flow fronts arrive hotter and with more energy. This allows the polymer chains to diffuse and entangle more effectively across the seam. Higher packing pressure also helps by forcing the two fronts together, improving the density and integrity of the bond.

We once worked on a power tool handle made from glass-filled nylon. The part was failing the drop test, and a new mold wasn’t in the budget. We spent a day at the machine, methodically adjusting parameters. By raising the melt temperature by 20°C and increasing the packing pressure by 15%, we were able to improve the weld line strength enough to pass the test. It shows that what happens at the press is just as important as the design itself.

Key Processing Levers to Pull

Think of these four parameters as your main controls for weld line quality. They all work together to help the two melt fronts merge into a stronger, more seamless bond.

- Melt Temperature: This is often the most effective adjustment. A hotter melt flows more easily and loses heat more slowly. When the two fronts meet, they are still very fluid, promoting better molecular entanglement. You need to be careful not to exceed the material’s degradation temperature, but pushing it towards the higher end of the recommended range is beneficial.

- Mold Temperature: A warmer mold surface prevents the plastic from freezing off too quickly as it flows. This keeps the melt fronts hotter and more mobile when they meet. It also gives the molecules more time to bond before the part solidifies, resulting in a less visible and stronger weld line.

- Injection Speed: A faster injection fills the mold more quickly, minimizing the time the plastic has to cool down before the weld line is formed. This helps maintain melt temperature. It can also influence fiber orientation, though the effect can be complex and may require some experimentation to get right.

- Packing Pressure and Time: After the mold is filled, the packing phase is crucial. Applying high packing pressure for an adequate amount of time physically pushes the two flow fronts together, squeezing out any trapped air and improving the density of the material at the weld line. This mechanical forcing enhances the bond.

A Balanced Approach

It’s important to understand that these parameters are interconnected. For example, increasing injection speed too much can lead to excessive shear heating, potentially degrading the material. The key is to make systematic, one-at-a-time adjustments and document the results.

| Parameter | Low Setting Effect | High Setting Effect | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Melt Temperature | Poor flow, weak bond | Better flow, stronger bond | Increase within material specs |

| Mold Temperature | Fast cooling, weak bond | Slower cooling, stronger bond | Increase to improve molecular diffusion |

| Injection Speed | Slow fill, premature cooling | Fast fill, maintains heat | Increase to minimize cooling during fill |

| Packing Pressure | Low density, poor fusion | High density, better fusion | Increase to mechanically improve the bond |

By methodically fine-tuning these settings, you can often achieve a significant improvement in weld line strength without making any changes to the mold or material.

Which Materials Are Best for Minimizing Weld Line Weakness?

You’ve optimized the mold design and dialed in the process, but you’re still not getting the performance you need. It might be time to look at the material itself. Are some fiber-reinforced plastics inherently better than others at forming strong weld lines?

Yes, the choice of base polymer and fiber type has a major impact on weld line strength. Amorphous polymers like polycarbonate (PC) and ABS tend to form stronger weld lines than semi-crystalline polymers like nylon (PA) or polypropylene (PP). This is because amorphous materials have a broader melt temperature range, allowing for better molecular entanglement as the flow fronts meet. Additionally, using shorter fibers or lower fiber concentrations can also improve weld line integrity.

I worked with a client developing an outdoor electronic enclosure. They were using a 30% glass-filled polypropylene, and it was failing impact tests right at the weld line. We suggested they switch to a 20% glass-filled PC/ABS blend. Even though the overall material stiffness was slightly lower, the amorphous nature of the PC/ABS allowed for a much stronger weld line. The new material passed the impact test with flying colors. It was a perfect example of choosing a material for its performance at the weakest point, not just on a datasheet.

Amorphous vs. Semi-Crystalline Polymers

This is the most important distinction when it comes to weld line performance. The molecular structure of the base resin dictates how well it can heal itself at a seam.

- Amorphous Polymers (PC, ABS, PSU): These materials have a randomly organized molecular structure. They soften gradually over a wide temperature range. This "gummy" state allows polymer chains from opposing flow fronts to diffuse and intermingle extensively before the material solidifies, creating a relatively strong bond.

- Semi-Crystalline Polymers (PA, PP, PBT, POM): These materials have highly ordered, crystalline structures mixed with amorphous regions. They have a sharp melting point and solidify very quickly once they fall below it. This rapid transition leaves very little time for the molecules at the weld line to entangle, resulting in a structurally weak interface.

| Polymer Type | Weld Line Strength | Common Examples | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amorphous | Generally Good to Excellent | PC, ABS, PC/ABS, PMMA | Housings, lenses, parts needing cosmetic surfaces and good impact strength. |

| Semi-Crystalline | Generally Poor to Fair | PA66, PP, PBT, POM | Gears, bearings, parts needing chemical resistance and low friction. |

The Role of Fibers and Fillers

The type and amount of reinforcement also play a huge role.

- Fiber Length: Long-fiber reinforced thermoplastics (LFRT) offer superior strength and stiffness in the bulk of the part but often create weaker weld lines than their short-fiber counterparts. The long fibers are simply less able to orient themselves favorably or bridge the knit line. If weld line strength is your primary concern, a material with shorter glass fibers (SGF) may be a better choice.

- Fiber Concentration: Higher fiber content (e.g., 40% glass fill vs. 20%) leads to greater strength overall but can worsen the weld line problem. With more fibers, there is less resin available to form a good bond, and the fibers themselves present a greater barrier to flow front fusion. Reducing the fiber percentage, if your application allows, can lead to a stronger weld line.

When selecting a material, don’t just look at the headline numbers on the datasheet. Consider the nature of the polymer and the reinforcement package to make an informed choice that accounts for the weakest point in your part.

Conclusion

We’ve seen that fiber reinforcement creates a significant challenge at weld lines, but it’s a manageable one. By strategically combining smart mold design, precise process control, and informed material selection, you can overcome this inherent weakness and produce strong, reliable parts that perform exactly as intended.